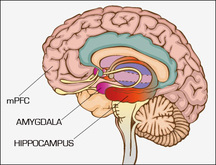

by Fate is defined in dictionary as “that principle or determining cause or will by which things in general are supposed to come to be as they are or events to happen as they do; the necessity of nature.” One of essential characteristics of fate is its predictability. Prediction is possible wherever there are structures, since structure determines function or action. Personality (character structure) is one such structure, which is formed as a result of conflict between culture and nature, between the instinctual needs of the child and the demands of the culture acting through parents. It is maintained by chronic contraction of musculature in the body. Chronic tension in the musculature reflects superego inhibition against the expression of certain feelings. In the beginning the tension was consciously created to block the expression of an impulse that could evoke a hostile response from our parents. Thus the fate of person can be predicted from their character structure. Can we escape our fate? The short answer is no! We cannot escape our fate for as long as our character structure remains fixed, our fate remains inescapable. Any attempt therefore to alter our fate is doomed to fail, and must fail as I will explain below. A primary goal of therapy therefore is to get the client to stop struggling against himself (fate). But by struggling against our fate we will ensure that our fate is fulfilled. We can only change our fate by accepting it. Ironically acceptance allows our fate (character structure) to change. In 1949, Donald Hebb, a Canadian neuropsychologist, wrote what has become known as Hebbian axiom: “Neurons that fire together wire together.” Each experience we encounter, whether a feeling, a thought, a sensation—and especially those that we are not aware of—is embedded in thousands of neurons that form a network. Repeated experiences become increasingly embedded in this network, making it easier for the neurons to fire (respond to the experience), and more difficult to unwire or rewire them to respond differently. Brain is thus shaped by experience.  Brain can be thought of as an informations processing organ, in the sense that when faced with a stimulus, it performs very fast correlation-like operations with what it has stored in memory to find the closest match to the stimulus just encountered. The correlations are performed with stored events that contain more information – are more emotionally significant. Emotional significance is marked by Amygdala – an almond-shape set of neurons located deep in the brain's medial temporal lobe (one in each hemisphere), very close to Hippocampus which manages organizing, storing and retrieving memories. In humans and other animals, this subcortical brain structure is linked to both fear responses and pleasure. Amygdalae therefore assign emotional significance and information to stimuli. Once the closest match is determined the emotional response will essentially be the same as the response corresponding to the past experience with some modifications. This is how we repeat our past, and fulfill our fate. Freud called this phenomenon “Repetition Compulsion”, or the compulsion to repeat past trauma. Note that any attempt to avoid our fate (past trauma) results in strengthening of the same neural networks. The reason for this is that in trying to avoid our fate we activate the same neural networks, which will be strengthened (Hebbian axiom). However, by accepting our fate we will reduce the emotional significance (information content) of our past experiences resulting in the possibility of change. When we accept our fate, brain may no longer quickly match a stimulus to what it has stored based on past experience. This may then result in formation of new neural networks that adapt to the new stimulus. The new experience when repeated, reactivates these new neural networks which will then get stronger until they become the dominant networks and result in reshaping our brain (Hebbian axiom). Thus it is by acceptance of our fate that we can change it, and change our character structure. AMYGDALA - The amygdala (Latin, corpus amygdaloideum) is an almond-shape set of neurons located deep in the brain's medial temporal lobe. Shown to play a key role in the processsing of emotions, the amygdala forms part of the limbic system. In humans and other animals, this subcortical brain structure is linked to both fear responses and pleasure. Its size is positively correlated with aggressive behavior across species. In humans, it is the most sexually-dimorphic brain structure, and shrinks by more than 30% in males upon castration. Conditions such as anxiety, autism, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and phobias are suspected of being linked to abnormal functioning of the amygdala, owing to damage, developmental problems, or neurotransmitter imbalance. Joseph E. LeDoux, PhD, is a neuroscientist whose research is primarily focused on the biological underpinnings of emotion and memory, especially brain mechanisms related to fear and anxiety. The present findings suggest a new technique to target specific fear memories and prevent the return of fear after extinction training. Using two recovery assays, we demonstrated that extinction conducted during the reconsolidation window of an old fear memory prevented the spontaneous recovery or the reinstatement of fear responses, an effect that was maintained a year later. Moreover, this manipulation selectively affected only the reactivated conditioned stimulus while leaving fear memory to the other non-reactivated conditioned stimulus intact. It has been suggested that the adaptive function of reconsolidation is to allow old memories to be updated each time they are retrieved. In other words, our memory reflects our last retrieval of it rather than an exact account of the original event. Daniela Schiller, Associate Professor, Mount Sinai Hospital on groundbreaking research on memory , and whether we might enable us to block highly traumatic memories. Here is a good article on this same subject published in New Yorker by Daniela Schiller: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/05/19/partial-recall Temporal error detection triggers memory reconsolidation (From Joseph LeDoux's lab at NYU)9/23/2015

"The retrieval of previously formed memory triggers the lability of that memory for a short time and its reconsolidation." Updating memories is critical for adaptive behaviors, but the rules and mechanisms governing that process are still not well defined. During a limited time window, the reactivation of consolidated aversive memories triggers memory lability and induces a plasticity-dependent reconsolidation process in the lateral amygdala (LA). However, whether new information is necessary for initiating reconsolidation is not known. Here we show that changing the temporal relationship between the conditioned (CS) and unconditioned (US) stimulus during reactivation is sufficient to trigger synaptic plasticity and reconsolidation of an aversive memory in the LA. These findings demonstrate that time is a core part of the CS-US association, and that new information must be presented during reactivation in order to trigger LA-dependent reconsolidation processes. In sum, this study provides new basic knowledge about the precise rules governing memory reconsolidation of aversive memories that might be used to treat traumatic memories. Joseph E. LeDoux, PhD, is an neuroscientist whose research is primarily focused on the biological underpinnings of emotion and memory, especially brain mechanisms related to fear and anxiety. Antonio Damasio, M.D. is a Professor of Neuroscience at the University of Southern California and an Adjunct Professor at the Salk Institute Dr. Damasio is the author of several books. An emotion consists of a very well orchestrated set of alterations in the body. Its purpose is to make life more survivable by taking care of a danger or taking advantage of an opportunity. Question: What is happening in our brain when we feel an emotion?Antonio Damasio: Feeling of an emotion is a process that is distinct from having the emotion in the first place. So it helps to understand what is an emotion, what is a feeling, we need to understand what is an emotion. And the emotion is the execution of a very complex program of actions. Some actions that are actually movements, like movement that you can do, change your face for example, in fear, or movements that are internal, that happen in your heart or in your gut, and movements that are actually not muscular movements, but rather, releases of molecules. Say, for example, in the endocrine system into the blood stream, but it's movement and action in the broad sense of the term.And an emotion consists of a very well orchestrated set of alterations in the body that has, as a general purpose, making life more survivable by taking care of a danger, of taking care of an opportunity, either/or, or something in between. And it's something that is set in our genome and that we all have with a certain programmed nature that is modified by our experience so individually we have variations on the pattern. But in essence, your emotion of joy and mine are going to be extremely similar. We may express them physically slightly differently, and it's of course graded depending on the circumstance, but the essence of the process is going to be the same, unless one of us is not quite well put together and is missing something, otherwise it's going to be the same.And it's going to be the same across even other species. You know, there's a, you know, we may smile and the dog may wag the tail, but in essence, we have a set program and those programs are similar across individuals in the species.Then the feeling is actually a portrayal of what is going on in the organs when you are having an emotion. So it's really the next thing that happens. If you have just an emotion, you would not necessarily feel it. To feel an emotion, you need to represent in the brain in structures that are actually different from the structures that lead to the emotion, what is going on in the organs when you're having the emotion. So, you can define it very simply as the process of perceiving what is going on in the organs when you are in the throws of an emotion, and that is achieved by a collection of structures, some of which are in the brain stem, and some of which are in the cerebral cortex, namely the insular cortex, which I like to mention not because I think it's the most important, it's not. I actually don't think it's the number one structure controlling our feelings, but I like to mention because it's something that people didn't really know about and many years ago, which probably now are going close to 20 years ago, I thought that the insular would be an important platform for feelings, that's where I started. And it was a hypothesis and it turns out that the hypothesis is perfectly correct. And 10 years ago, we had the first experiments that showed that it was indeed so, and since then, countless studies have shown that when you're having feelings of an emotion or feelings of a variety of other things, the insular is active, but it doesn't mean that it's the only thing that is active and there are other structures that are very important as well. Why do we crave love so much, even to the point that we would die for it? To learn more about our very real, very physical need for romantic love, Helen Fisher and her research team took MRIs of people in love — and people who had just been dumped. Anthropologist Helen Fisher studies gender differences and the evolution of human emotions. She's best known as an expert on romantic love, and her beautifully penned books — including Anatomy of Love and Why We Love — lay bare the mysteries of our most treasured emotion. Helen Fisher's courageous investigations of romantic love -- its evolution, its biochemical foundations and its vital importance to human society -- are informing and transforming the way we understand ourselves. Fisher describes love as a universal human drive (stronger than the sex drive; stronger than thirst or hunger; stronger perhaps than the will to live), and her many areas of inquiry shed light on timeless human mysteries, like why we choose one partner over another. Almost unique among scientists, Fisher explores the science of love without losing a sense of romance: Her work frequently invokes poetry, literature and art -- along with scientific findings -- helping us appreciate our love affair with love itself. In her research, and in books such as Anatomy of Love, Why We Love, and her latest work Why Him? Why Her?: How to Find and Keep Lasting Love, Fisher looks at questions with real impact on modern life. Her latest research raises serious concerns about the widespread, long-term use of antidepressants, which may undermine our natural process of attachment by tampering with hormone levels in the brain. Social media is dominating most of our attention throughout the day. Yet, is it truly changing our face-to-face relationships? Dr. Dan Siegel, clinical professor of psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine reveals how social media is actually physically rewiring our brains. Dr. Allan Schore on hypo-arousal, hyper-arousal, dissociation and the inability to take in comfort7/23/2015

Dr. Allan Schore is on the clinical faculty of the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, and at the UCLA Center for Culture, Brain, and Development. Dr Schore's contributions appear in multiple disciplines, including developmental neuroscience, psychiatry, psychoanalysis, developmental psychology, attachment theory, trauma studies, behavioral biology, clinical psychology, and clinical social work. His groundbreaking integration of neuroscience with attachment theory has led to his description as "the American Bowlby," with emotional development as "the world’s leading authority on how our right hemisphere regulates emotion and processes our sense of self," and with psychoanalysis as "the world's leading expert in neuropsychoanalysis." Antonio Damasio, M.D. is David Dornsife Professor of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Neurology, and director of the Brain and Creativity Institute at the University of Southern California. From one of the most significant neuroscientists at work today, a pathbreaking investigation of a question that has confounded philosophers, psychologists, and neuroscientists for centuries: how is consciousness created? Dr. Antonio Damasio has spent the past thirty years studying and writing about how the brain operates, and his work has garnered acclaim for its singular melding of the scientific and the humanistic. In Self Comes to Mind, he goes against the long-standing idea that consciousness is somehow separate from the body, presenting compelling new scientific evidence that consciousness—what we think of as a mind with a self—is to begin with a biological process created by a living organism. Besides the three traditional perspectives used to study the mind (the introspective, the behavioral, and the neurological), Damasio introduces an evolutionary perspective that entails a radical change in the way the history of conscious minds is viewed and told. He also advances a radical hypothesis regarding the origins and varieties of feelings, which is central to his framework for the biological construction of consciousness: feelings are grounded in a near fusion of body and brain networks, and first emerge from the historically old and humble brain stem rather than from the modern cerebral cortex. Dr. Damasio suggests that the brain's development of a human self becomes a challenge to nature's indifference and opens the way for the appearance of culture, a radical break in the course of evolution and the source of a new level of life regulation—sociocultural homeostasis. He leaves no doubt that the blueprint for the work-in-progress he calls sociocultural homeostasis is the genetically well-established basic homeostasis, the curator of value that has been present in simple life-forms for billions of years. Self Comes to Mind is a groundbreaking journey into the neurobiological foundations of mind and self. Dr. Antonio Damasio is a Professor of Neuroscience at the University of Southern California and an Adjunct Professor at the Salk Institute Dr. Damasio is the author of several books and heads the Brain and Creativity Institute. His book "Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain", explores the relationship between the brain and consciousness. "Antonio Damasio's research in neuroscience has shown that emotions play a central role in social cognition and decision-making" Books:

|

AuthorHomayoun Shahri Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

Ravonkavi Privacy Policy

©2018 Ravonkavi

©2018 Ravonkavi

RSS Feed

RSS Feed