|

The Science of Compassion: Origins, Measures, and Interventions, which took place July 19th to 22nd in Telluride Colorado, was the first large-scale international conference of its kind dedicated to scientific inquiry into compassion. The conference convened a unique group of leading world experts in the fields of altruism, compassion, and service to present their latest research. This talk was part of panel Origins and Conceptual Models of Compassion by Stephen Porges, Ph.D. Dr. Dan Siegel of the Mindsight Institute discusses the neurological basis of behavior, the mind, the brain and human relationships in the contect of cities. He explains one definition of the mind as "an embodied and relational emergent process that regulates the flow of energy and information," and describes the role of awareness and attention in monitoring and modifying the mind. He recommends using the notion of health as a means of linking individual, community and planetary wellbeing. Dr. Allan Schore is on the clinical faculty of the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, and at the UCLA Center for Culture, Brain, and Development. Dr Schore's contributions appear in multiple disciplines, including developmental neuroscience, psychiatry, psychoanalysis, developmental psychology, attachment theory, trauma studies, behavioral biology, clinical psychology, and clinical social work. His groundbreaking integration of neuroscience with attachment theory has led to his description as "the American Bowlby," with emotional development as "the world’s leading authority on how our right hemisphere regulates emotion and processes our sense of self," and with psychoanalysis as "the world's leading expert in neuropsychoanalysis." Dr. Siegel is currently clinical professor of psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine where he is on the faculty of the Center for Culture, Brain, and Development and the founding co-director of the Mindful Awareness Research Center. Dr. Allan Schore is on the clinical faculty of the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, and at the UCLA Center for Culture, Brain, and Development. He is author of four seminal volumes,Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self, Affect Dysregulation and Disorders of the Self, Affect Regulation and the Repair of the Self, and The Science of the Art of Psychotherapy, as well as numerous articles and chapters. His Regulation Theory, grounded in developmental neuroscience and developmental psychoanalysis, focuses on the origin, psychopathogenesis, and psychotherapeutic treatment of the early forming subjective implicit self. From:

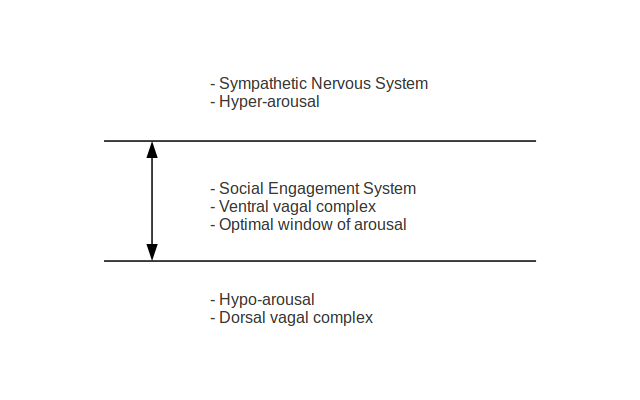

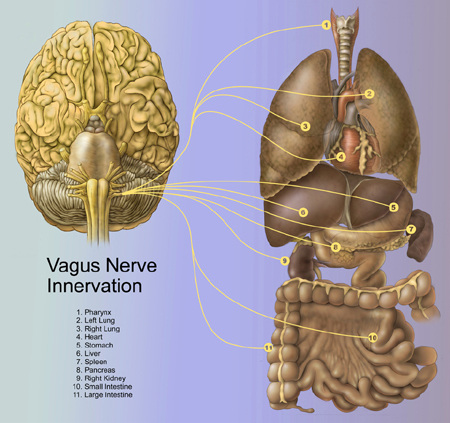

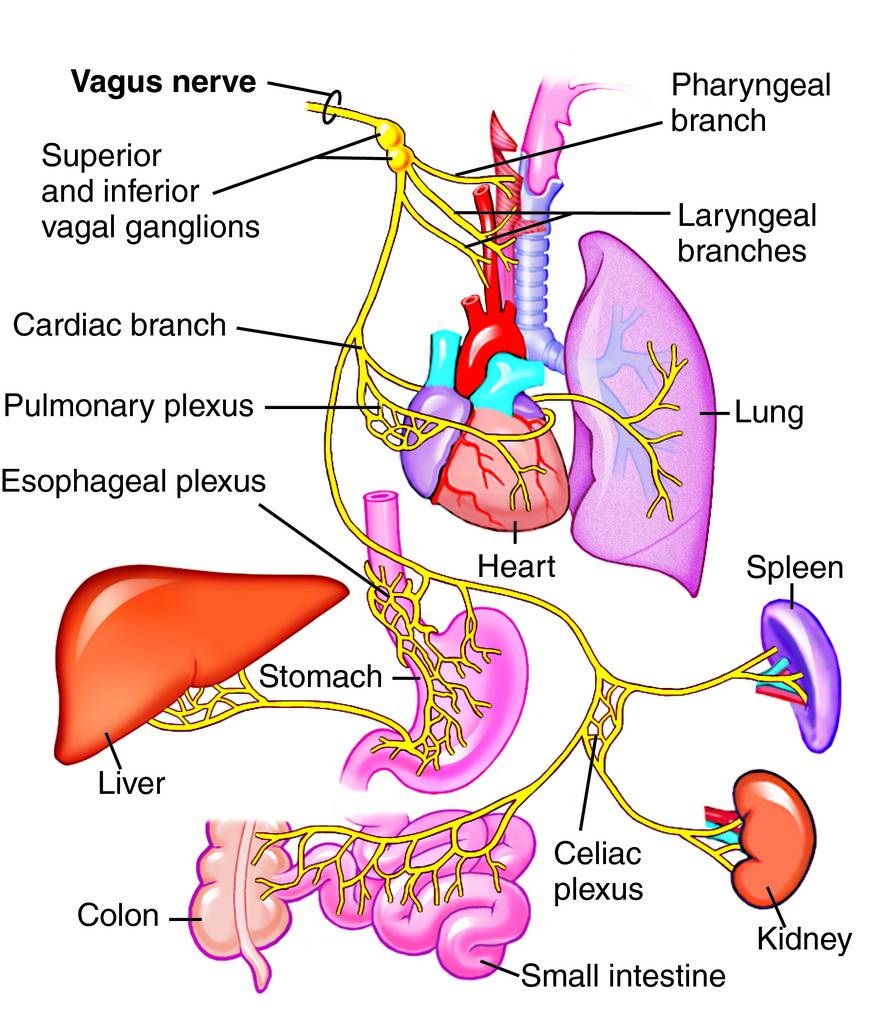

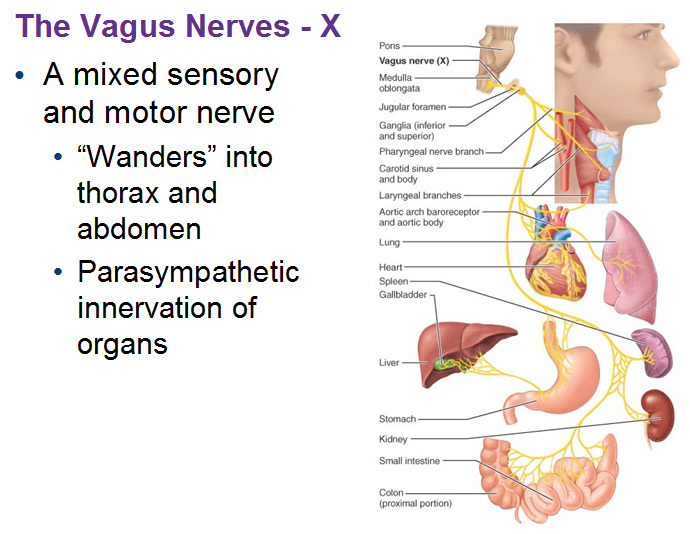

Polyvagal theory Before I introduce the polyvagal theory, I will first briefly discuss the human nervous system in order to introduce the prerequisites to understanding the polyvagal theory. The human nervous system is divided into two branches; the peripheral nervous system, and the central nervous system (spinal cord). The peripheral nervous system is further divided into somatic-sensory nervous system, and the autonomic nervous system. Somatic nervous system is further divided into motor (efferents), and sensory (afferent) nerves. The autonomic nervous system is divided into two branches, the parasympathetic nervous system and the sympathetic nervous system. The parasympathetic nervous system has two main components: the first branch is controlled by the dorsal vagus nerve, “… characterized by a primitive unmyelinated visceral vagus that controls digestion, and responds to threats by depressing metabolic activities and is behaviorally associated with immobilization and freeze behavior” (Porges, 2001, p. 123). The second branch is controlled by the ventral vagal nerve and is unique to mammals, and according to Porges (2011): The VVC has primary control of supradiaphragmatic visceral organs including the larynx, pharynx, bronchi, esophagus, and heart. […] In mammals, visceromotor fibers of the heart express high levels of tonic control and are capable of rapid shifts in cardioinhibutory tone to provide dynamic changes in metabolic output to match environmental challenges. (p. 160) The other branch of the autonomic nervous system is the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). The sympathetic nervous system is capable of increasing metabolic output and inhibiting the dorsal vagus nerve, thus increasing mobilization behaviors necessary for fight and flight (Porges, 2001). The more primitive life forms use the unmyelinated dorsal vagal complex (DVC), and the sympathetic nervous system to modulate cardiac output and mobilization, or freeze responses. Mammals on the other hand, in order to survive, had to tell the difference and distinguish a friend from a foe, determine and evaluate the safety of their environment, and communicate with their community. Ventral vagus complex (VVC) is the response to these evolutionary needs. The myelinated ventral vagus complex characterizes our social engagement system, which is responsible for facial muscles (emotional), eyelid opening (looking), middle ear muscles (extracting human voice from background noise), muscles of ingestion, muscles of vocalization and language, and head turning muscles (Porges, 2001). In more primitive life forms (pre-mammals), the dorsal vagal complex and the sympathetic nervous system have the opposing functions of decreasing and increasing cardiac output respectively, and thus modulate mobilization. In mammals, with the evolution of the ventral vagal complex, the cardiac output is modulated without the engagement of the former more primitive systems. Thus activation of the myelinated vagal system can result in temporary mobilization and expression of the sympathetic tone without requiring the activation of sympathetic or adrenal system (Porges, 2011). The ventral vagal complex, therefore, acts as a break on cardiac output, capable of rapid changes in heart rate, resulting in mobilizing or calming the individual. Polyvagal theory (Porges, 2011) proposes a hierarchical organization of autonomic nervous system. When a system higher in hierarchy fails, then a more primitive branch of the autonomic system engages. We thus have the following: At the top of the hierarchy is the ventral vagal complex (VVC), a mammalian signaling system for motion, emotion, and communication. The second complex in the hierarchy is the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which is an adaptive mobilization system engaged during fight or flight behaviors. Finally, the dorsal vagal complex (DVC) is the immobilization system (Porges, 2011). Figure 2 shows the three zones of arousal and the window of tolerance within which the social engagement system (ventral vagal complex) is activated. When someone is hyper-aroused, the person experiences too much arousal to process information effectively, and is usually overwhelmed and disturbed by intrusive images, feelings, affects, and body sensations. When the person is hypo-aroused, he/she experiences something different, namely, a downward modulation of emotions and sensations – a numbing, a sense of deadness or emptiness, passivity, and possibly paralysis. On the other hand, people with a narrow window of tolerance (the middle region in Figure 2), experience fluctuations in emotions and feelings as unmanageable and dysregulating. Most traumatized people have a narrow window of tolerance, and can easily shift into hypo/hyper- arousal states by normal fluctuations in arousal (Ogden, Minton, & Pain, 2006). It is also very important to mention that the states depicted in Figure 2 are not mutually exclusive, in that one can simultaneously be both hyper-aroused, and hypo-aroused – which would be experienced as being highly aroused (ready for action) but unable to move. It is also possible to be in the optimal zone of arousal (activation of our social engagement system) yet experience elements of hypo/hyper-arousal. Also I must note that the boundaries between these zones are not very rigid, and depend on, among other things, emotional state (energetic state) of the mind- body. References Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. Porges, S. (2001). The polyvagal theory: phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 42, 123-146. Porges, S. (2011). The polyvagal theory. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. Figure 2 Optimal Window of Arousal HEALTH, LONGEVITY & AGING - As you get older, your immune system produces more inflammatory molecules, and your nervous system turns on the stress response, promoting system breakdown and aging.

That’s not just talk. It’s backed by scientific studies. For example, Kevin Tracey, the director of the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, discovered how the brain controls the immune system through a direct nerve-based connection. He describes this as the inflammatory reflex (i). Simply put, it is the way the immune system responds to the mind. Let me explain. You immune system is controlled by a nerve call the vagus nerve. But this isn’t just any nerve. It is the most important nerve coming from the brain and travels to all the major organs. And you can activate this nerve — through relaxation, meditation, and other ancient practices, such as the Mayan system of Light Language, combined with Vagus Nerve Activation Techniques given recently by the Group & Steve Rother, the Vagus Nerve can be activated and worked with energetically through geometry, frequency, color, and light. What’s the benefit of that? Well, by activating the vagus nerve, you can control your immune cells, reduce inflammation, and even prevent disease and aging! It’s true. By creating positive brain states — as meditation masters have done for centuries — you can switch on the vagus nerve and control inflammation. You can actually control your gene function by this method. Activate the vagus nerve, and you can switch on the genes that help control inflammation. Inflammation is one of the central factors of disease and aging. Original article by Angela Savitri Petersen STRESS & THE VAGUS NERVE Your body’s levels of stress hormones are regulated by the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS has two components that balance each other, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS).

The SNS turns up your nervous system. It helps us handle what we perceive to be emergencies and is in charge of the flight-or-fight response. The PNS turns down the nervous system and helps us to be calm. It promotes relaxation, rest, sleep, and drowsiness by slowing our heart rate, slowing our breathing, constricts the pupils of our eyes, increases the production of saliva in our mouth, and so forth. The vagus nerve is the nerve that comes from the brain and controls the parasympathetic nervous system, which controls your relaxation response. And this nervous system uses the neurotransmitter, acetylcholine. If your brain cannot communicate with your diaphragm via the release of acetylcholine from the vagus nerve (for example, impaired by botulinum toxin), then you will stop breathing and die. Acetylcholine is responsible for learning and memory. It is also calming and relaxing, which is used by vagus nerve to send messages of peace and relaxation throughout your body. New research has found that acetylcholine is a major brake on inflammation in the body. In other words, stimulating your vagus nerve sends acetylcholine throughout your body, not only relaxing you but also turning down the fires of inflammation which is related to the negative effects from stress. Exciting new research has also linked the vagus nerve to improved neurogenesis, increased BDNF output (brain-derived neurotrophic factor is like super fertilizer for your brain cells) and repair of brain tissue, and to actual regeneration throughout the body. Original article by Angela Savitri Petersen Original article by Angela Savitri Petersen

WHAT IS THE VAGUS NERVE?The 10th of the cranial nerves, it is often called the “Nerve of compassion” because when it’s active, it helps create the “warm-fuzzies” that we feel in our chest when we get a hug or are moved by something… The vagus nerve is a bundle of nerves that originates in the top of the spinal cord. It activates different organs throughout the body (such as the heart, lungs, liver and digestive organs). When active, it is likely to produce that feeling of warm expansion in the chest—for example, when we are moved by someone’s goodness or when we appreciate a beautiful piece of music. Neuroscientist Stephen W. Porges of the University of Illinois at Chicago long ago argued that the vagus nerve is [the nerve of compassion] (of course, it serves many other functions as well). Several reasons justify this claim. The vagus nerve is thought to stimulate certain muscles in the vocal chamber, enabling communication. It reduces heart rate. Very new science suggests that it may be closely connected to receptor networks for oxytocin, a neurotransmitter involved in trust and maternal bonding. Our research and that of other scientists suggest that activation of the vagus nerve is associated with feelings of caretaking and the ethical intuition that humans from different social groups (even adversarial ones) share a common humanity. People who have high vagus nerve activation in a resting state, we have found, are prone to feeling emotions that promote altruism—compassion, gratitude, love and happiness. Arizona State University psychologist Nancy Eisenberg has found that children with high-baseline vagus nerve activity are more cooperative and likely to give. This area of study is the beginning of a fascinating new argument about altruism: that a branch of our nervous system evolved to support such behavior. |

AuthorHomayoun Shahri Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

Ravonkavi Privacy Policy

©2018 Ravonkavi

©2018 Ravonkavi

RSS Feed

RSS Feed